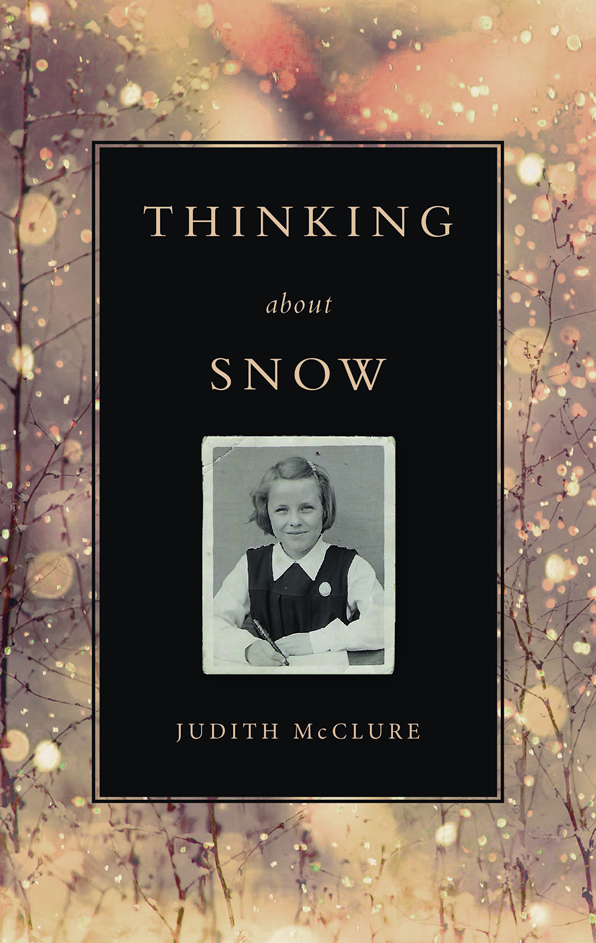

Judith McClure, headteacher at St George’s School in Edinburgh from 1994 until 2009, was enormously respected by comprehensive heads for her frequent (but unique) cooperation with their sector. Her memoir, ‘Thinking About Snow’ (published by Maclean Dubois) explores the moulding of such an astute and admired educationalist.

She was the third child, and only daughter, of a Catholic detective sergeant in post-war Middlesbrough. Her loving home, where faith was explicit and ever-present, also nurtured her love of learning. Her primary schooling in the 1950s consisted of interrogation about attendance at Mass, preparation for First Communion, raising money for overseas missions, screening from non-Catholic children, rote learning, incessant testing and ‘an emphasis on accuracy rather than imagination.’

She progressed to a convent grammar school, with enforced uniform, which demanded expectations and daily religious instruction. Her rebellious streak, however, found the curriculum repetitive, unchallenging and dull. She rejected university, deciding instead to become a solicitor’s articled clerk. Prior to moving to study at the college of law, Mother Mary Monica, her former headteacher intervened, suggesting two potential London residences. She opted for More House, run by the Canonesses of St Augustine, nuns dedicated to education as well as poverty, chastity and obedience.

A devout Catholic upbringing and attendance at challenging and demanding Catholic schools had left Judith McClure on a spiritual search for a purpose in life. Her year in More House convinced her that becoming a nun was the means to find that purpose.

Becoming a postulant meant that her parents saw her for a monthly hour-and-a-half visit. All mail was read by the novice mistress. Silence was observed for most of the day. Life was impeccably disciplined. Again, a rebellious instinct surfaced. Why, in this well-ordered community of religious women, was there ‘the absolute necessity of a male priest to celebrate Mass’? She questioned the class distinctions between professed and lay members of the community. She noted that the nun’s whip for flagellation, was to be applied to the bare back, ‘as if one were a donkey.’

Judith McClure’s crisis was intellectual – a questioning of absolute obedience and uncritical faith. She was being simultaneously introduced to Her Order’s teaching function – a role in which she revelled – and preparing for university entrance. Conformity was expected on the one hand, but intellectual exploration was necessary on the other – all of this when the Second Vatican Council, was exploring a somewhat more liberal perspective than Rome had ever previously contemplated.

In these briefly heady days she even ‘considered the reform of religious life and the possibility of female priests and bishops,’ but in 1968, Humanae Vitae reaffirmed Catholic teaching on birth control and abortion. ‘Once more women were to be instructed and obedience demanded.’ At the same time, Judith McClure obtained a place at Oxford, but was instructed to reside, not in college, but in an Oxford convent. The crisis had arrived and she concluded that enclosed religious life was ‘unnecessary, misguided and potentially damaging.’ With another nun, she left the convent and sought a new commitment in the world of education and teaching. The church’s loss was education’s gain.

Her 84-page narrative, spanning 24 years, is gentle, restrained and concise. A regimented and exam-focused school system, authoritarian assumptions of unquestioning obedience, and the subjection of women by male-centred institutions, are all held to account. She offers powerful insights into the psychology of a church which continues to insist that what is taught by the church must be believed and accepted by all its members.

What Judith McClure has displayed, in her book as in her professional life, as admirable and as the courageous antidote to unquestioning belief is the rigorous, unbounded and creative exploration of intellectual pursuits and openness to the widest range of experiences and traditions.

The above article first appeared in Scottish Review on 17 October 2018: http://www.scottishreview.net/AlexWood451a.html